On a warm summer afternoon, a teenager wandered through the tall grass that fringed the Grace Hartman Amphitheatre when an old transistor radio, half-hidden in the grass, caught her eye.

Curious, she flicked the switch and turned the dial slowly. With each click, a song floated out, transporting her back through time.

First, a soaring voice filled the air — Andrew Hyatt — one of the modern torchbearers of Northern Ontario’s music scene, carrying forward the festival’s legacy.

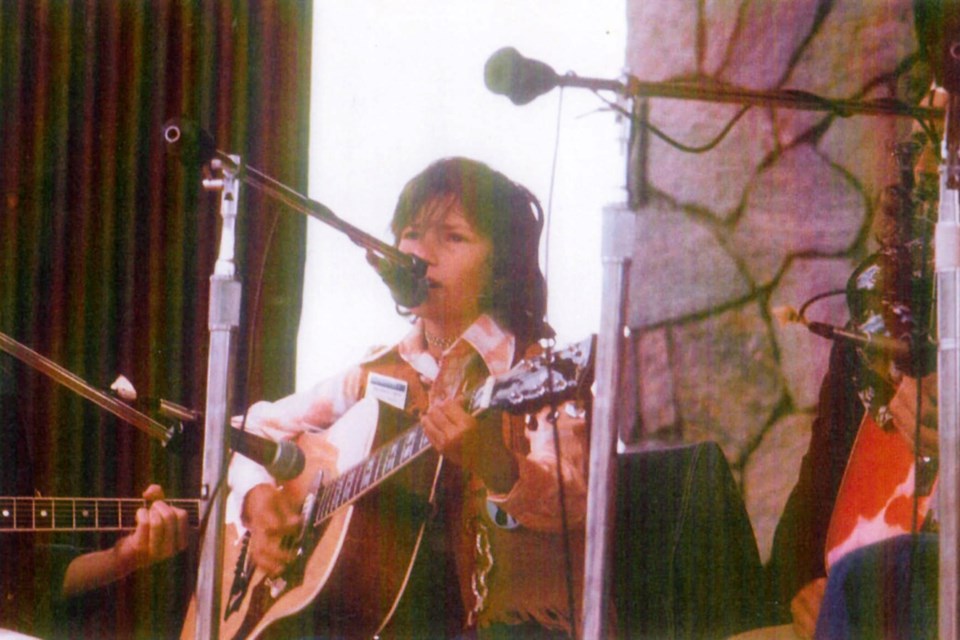

Then the air shimmered with the spirited melodies of Fred Eaglesmith and Valdy, their timeless folk tunes wrapping her in memories she never lived but somehow can feel deeply. Then she heard the intricate blues of Jackie Washington whose constant presence echoed through the years.

The radio hummed backward through decades — familiar names whispered in the breeze: Stan Rogers crafting Barrett’s Privateers, Jane Siberry’s haunting voice, the youthful energy of Shania Twain before she conquered the world.

Finally, the dial paused on the unmistakable sound of CANO, their voices weaving a warm invitation: «Viens raconter une histoire. Du bon vieux temps » (Come tell a story. Of the good old days).

And so, with the radio softly playing in her hand, we begin to listen to the story of the Northern Lights Festival Boréal, its history etched in the voices and memories from the past.

Nestled in the heart of Northern Ontario, amid the rugged landscape and sprawling forests of Sudbury, a unique cultural tradition has flourished for over half a century: the Northern Lights Festival Boréal (NLFB). More than just a folk music festival, NLFB embodies the spirit of the Cambrian frontier, offering a vibrant blend of music, art, community, and bilingual heritage.

For generations, it has been a gathering place for musicians and audiences alike, where the gentle strum of guitars, the pulse of the drum, and the soaring voices of folk artists have resonated under open skies.

From its humble beginnings in the early 1970s to becoming a celebrated cultural institution in Canada, NLFB has been shaped not only by its artists but also by the memories and voices of its audience and volunteers.

The Northern Lights Festival Boréal was born out of a desire to create a space in Northern Ontario where folk music, crafts, and community spirit could thrive. As Grace Hartman, former Mayor of Sudbury (and current namesake of the main stage for NLFB), wrote in a heartfelt letter to the editor after a visit in 1974, the event was a refreshing contrast to other festivals:

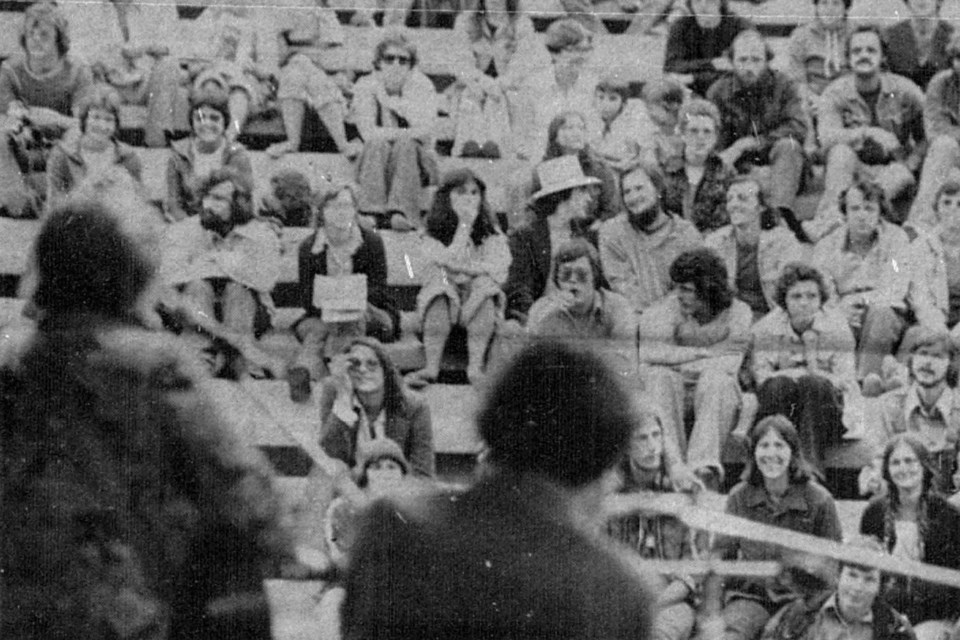

“While spending the past week-end in Sudbury I took the opportunity to attend the Northern Lights Folk Festival that was taking place at Bell Park Amphitheatre, and I was thrilled to see how this annual event has improved and expanded in scope since it was first introduced two years ago,” she said.

“I’s very comprehensive programme with something for everyone…is an indication of how much work has gone into its preparation and how generally popular it has become…There was every indication that the Festival was enjoyed by the many thousands who at tended. It seemed to be a success in every way and the group of young people who planned it deserve warmest congratulations and all possible encouragement in the future.”

Hartman’s words capture the optimism and energy that infused the festival’s formative years. Unlike some of the sprawling, commercialized festivals emerging elsewhere at the time, NLFB emphasized community participation, artistic integrity, and the unique northern culture.

In 1980, artistic co-director Michael Gallagher (along with Scott Merrifield) pointed out that the festival celebrated the bilingual heritage of the region, with roughly one-third of all performances and craftspeople coming from across Northern Ontario and Francophone artists regularly featured, reflecting a mandate to promote Northern talent and honor the festival’s bilingual foundation.

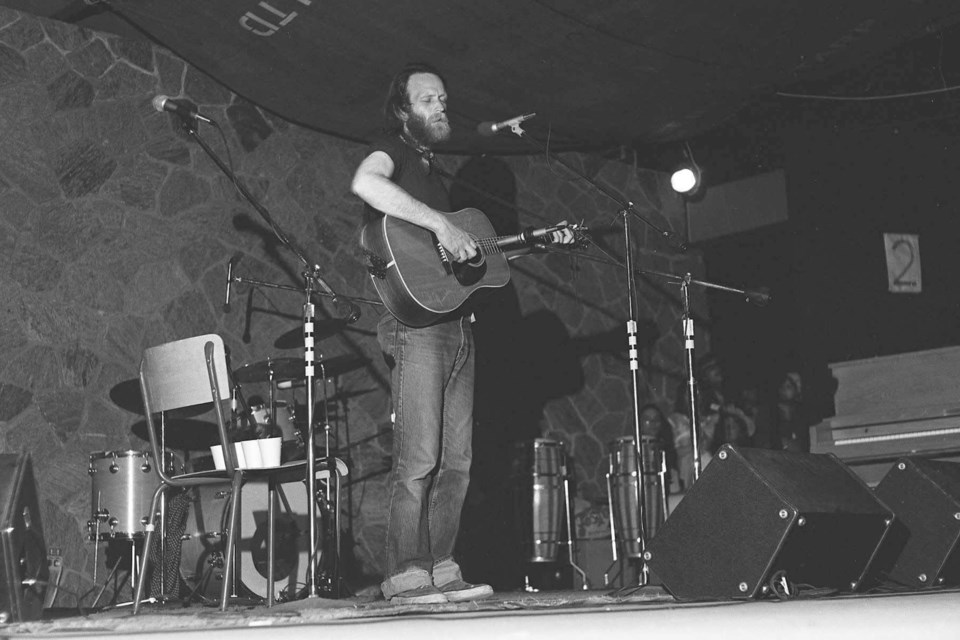

At its core, the Northern Lights Festival Boréal was always about music — but not just any music. It was about music with universal appeal, music that was genuine, heartfelt, and accessible to people of all ages.

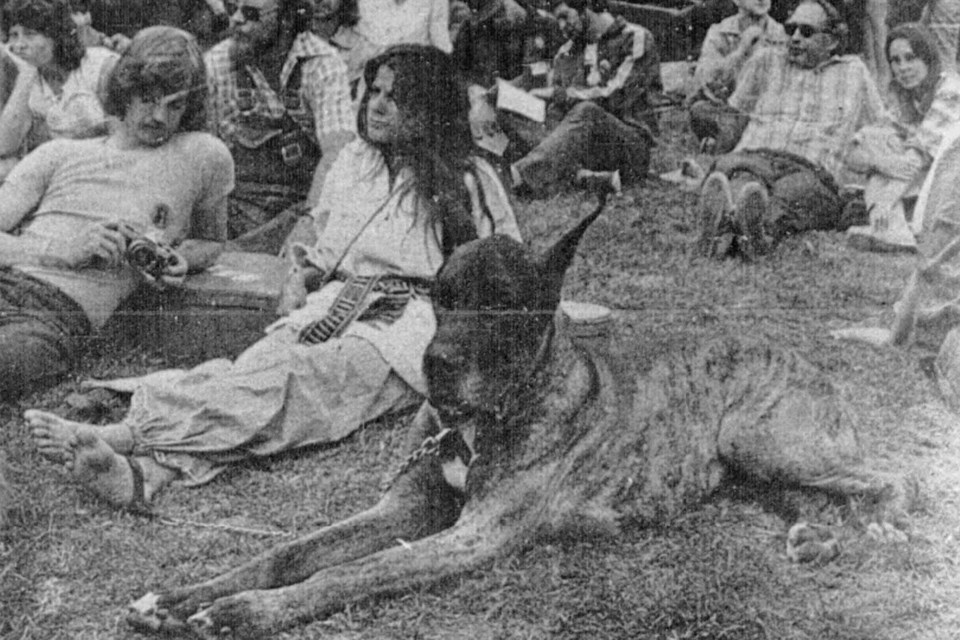

John Closs, the festival’s artistic director in the late 1970s, highlighted this ethos: “The music we're into has universal appeal, but there's nothing loud and commercial about it... It's a relaxed atmosphere... people enjoying themselves and listening to music. And, that's important.”

This relaxed, immersive environment cultivated an intimate connection between performers and audience, creating an atmosphere far removed from the commercial spectacle of many other music events.

By the mid-1970s, Fred Pawluk, organizer for the Northern Lights Folk Festival at the time, pointed out the quick growth in popularity of the NLFB. "We've been getting calls and letters from people as far away as the States who are on their way up to Sudbury and we anticipate a great weekend for all visitors.”

The essence of any festival lies in the memories of those who lived it. The Northern Lights Festival Boréal inspired countless memories that reflect its impact on individuals and families.

For Art Moses, the festival was a turning point, it contributed to a call to return home.

“Experiencing the electrifying performance of CANO in 1976 convinced me I should move back to my hometown Sudbury, which I did—for nine years,” he wrote.

CANO, the Franco-Ontarian progressive rock band, was a frequent presence at NLFB, bridging cultural divides and inspiring listeners with their energetic performances.

Volunteers like Jungle Jim (who commented at the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page) remember the festival as a vibrant hub of creativity and camaraderie.

His memory reminds us that the festival was as much about community building as it was about music, with local artisans showcasing their crafts alongside performances: “(it) was a great time back then, (I) volunteered at a few of them, great performers, artisans making guitars, forging things.”

Another past volunteer, Vic Thériault, also showed us the community building aspect as he “was the billeter at the first NLFB and the 25th.” (Though apparently Sneezey Waters and Jane Siberry sapped all of his energy at the 25th).

The nostalgia of other readers highlighted a golden era, lost to some spectators via the festival’s expansion, when the focus was tightly on authentic folk sounds and grassroots atmosphere.

Kenny Hill fondly wrote: “I have very fond memories of the NLFB in the last half of the ‘70s. It was so good.” While Jimmy Bald agreed and summed it up succinctly: “When it was a real folk festival with real music!”

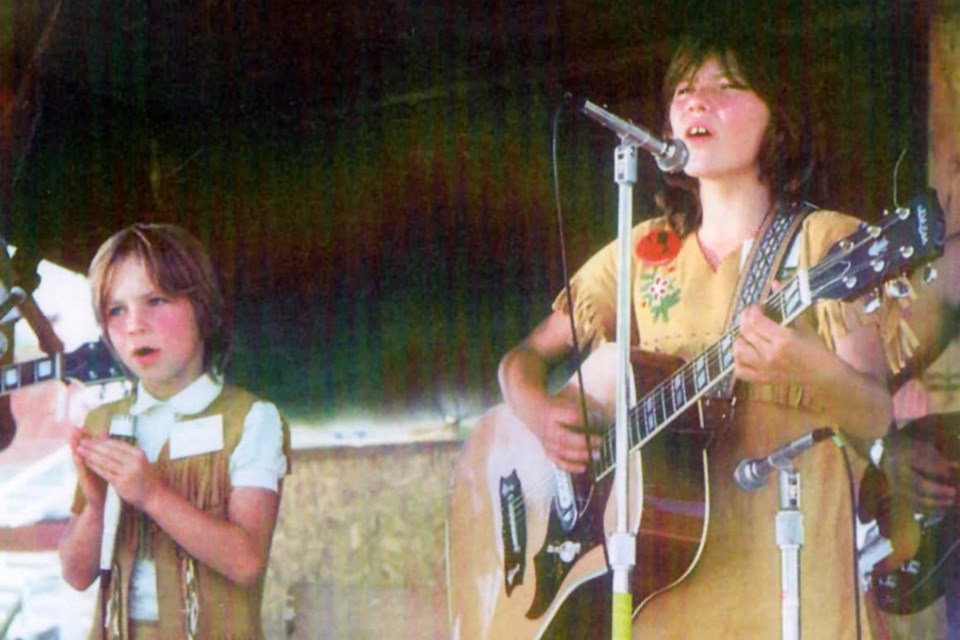

Joanne Jankowski’s memories bring us a specific moment of joy and also reveals the festival’s integration of local youth talent, creating a truly community-rooted experience. “In the first few years, I went to (all of) them. One year, we gave Valdy a standing ovation and he played an encore song for us all. I probably went there until 1977…’Nobody Special’ (with) members from Lasalle Secondary School, played also…Loved the years at the original amphitheatre and local acts performing too.”

Sometimes the festival’s magic even spilled out into the surrounding community. Astrid Colton recalls a story from 1977: “Valdy attended a wedding in Coniston that weekend too. My dad played guitar in the band at the wedding, until Valdy was asked to perform. My dad lent him his Gibson. Next day my dad told us what happened, but got the name wrong, called him Wally.”

Many other readers’ reminiscences also highlighted how much of an impact many of the recurring cast of characters (in this case, Valdy) had on NLFB visitors.

Eleanora Toddy Connors memory speaks to the close-knit and unpretentious atmosphere of the festival where one could just spend time with the performers as everyday people. “I remember sitting with Valdy and chatting before he went on.”

While Donald Lawrence added, “I remember seeing Valdy every year. And who can forget CANO. Good times were always to be had at the show.” And, Joanne Larocque enthuses that “seeing Valdy walk on stage during the Northern Lights Festival Boreal was something I’ll never forget. Special memories.”

Harvey Wyers was a stalwart attendee, showing how the NLFB became a yearly tradition for many: “I was there also, actually I didn’t miss a festival for the first 18 years. Became sporadic after that.”

Reader Faye Alatalo added that she “rarely missed a festival, (as) I was just moving back to Sudbury around that time. (c.1976).”

Rick Fowler’s memories highlight the festival’s educational and joyful aspects. Different workshops enriched the experience beyond passively listening, creating opportunities for audience participation and skill-building.

“I remember Beverly Lee Copeland and her incredible piano playing,” he wrote. “She did a songwriting workshop that was hard to forget. I remember Valdy playing his most popular tunes and also the Good Brothers who were very popular at the time. The total vibe was pretty joyful.”

For some, like reader MikeSamdra Maslakow, the festival was a family affair, integrating the rhythms of music and life.

“(I) was there (in 1975) with my two-year-old and very expectant with my second child.”

For others, like reader Holly Julian, the festival was not without its youthful rebellion and mischievous fun. “Ahh yes..I remember back in the day going with my boyfriend, he was the bass player in a little band here in Sudbury, I was responsible for sneaking the booze into the gig in my huge purse.”

Another reader, Ian Mc shared with us a classic youth pilgrimage tale, that highlights the festival’s draw all across Northern Ontario. “I remember hitchhiking from Haileybury to Sudbury, the people we met, and the great music. My most persistent memory is the t-shirt I bought with the last of my money. I kept it for over 20 years until it literally fell apart. We had a great time, even if the memory is a little foggy after all these years. (That's the ticket. Blame it on the time.)”

Terry Carrey McMahon who was a teenager at that time (mid-1970s) “loved it when it was free and you could walk around seeing the vendors. Those were the days.”

Behind the scenes, the festival continued to be shaped by passionate artistic directors and programmers who sought to balance local talent, Francophone artists, and renowned folk performers from across Canada.

Scott Merrifield, a founder and artistic director, previously recalled the 1976 festival vividly (after a post by Shania Twain celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the festival).

“I booked and programmed the festival in 1976,” he wrote, with specific emphasis on “a country workshop with Colleen Peterson, Eilleen (now Shania) Twain, Lawrence Martin who played with Shania, Robert Paquette, Stan Dueck, Nigel Russell, and Rick Whitelaw.” He also added, “Shania came back to Northern Lights a couple of years later, accompanied by her little sister, Carrie-Ann (while) Stan Rogers was also at the 76 festival where he wrote 'Barrett's Privateers'. Great memories!”

Reader James Burr recalls how during the early days of the festival the organizers, when faced with potential disaster, were able to pivot quickly and make sure that the show continued. “I remember Murray McLauchlan playing in '72 or '73. It rained hard and events at the amphitheatre had to be cancelled. The organizers huddled and announced the Festival was relocating to the Great Hall at Laurentian University. A few hours later, Murray performed a beautiful set to a crowd of wet fans sitting on the floor in front of the stage.”

Another early volunteer, Ray Auger, also remembered the intense early days:

“I remember those heady days and the long ‘meetings’ to discuss what might be possible. The CYC and Stig Puschel and how anything was possible. The first year unfolded like it was the tenth year and made us look like we knew what we were doing. As Stig would say, ‘Far out, man’.”

For many, the festival is not just an event but a symbol of Northern Ontario’s resilient spirit and cultural richness. It offers a welcoming space where generations dance, laugh, learn, and share in the magic of music. As Rosemary Kohr wrote:

“Sudbury & Northern Ontario are tough to describe to people who've never lived there. And Northern Lights Festival Boreal has that same magic. What great memories, eh?!”

Well, dear readers, the Northern Lights Festival Boréal remains a shining jewel in Sudbury’s cultural landscape. From its modest beginnings to its status as one of Canada’s premier folk festivals, it has reflected the hopes, creativity, and diversity of its people. It has launched careers, fostered community bonds, and inspired countless stories that weave together the fabric of Northern Ontario’s identity.

The voices of those who experienced the festival—artists, volunteers, audience members, and civic leaders—tell a story of a festival that grew organically from a community’s love of music and culture. It is a testament to the power of art to bring people together, to celebrate roots while embracing change, and to create memories that endure across decades.

But, before the transistor radio is turned off and we end our sentimental journey, I leave you with one last memory, from Sam Merrifield, who has been attending every year (except for 2-3) since he was born.

“A favourite memory of mine is from this year,” he said. “My brother Max Merrifield masterfully curated his last festival as artistic director after nine years this summer. And there we were: my mother Vickie McGauley (former artistic director), my father Scott Merrifield (a founder and former artistic director), my brother Max Merrifield (outgoing artistic director) and myself all dancing in the wind and rain with smiles on our faces and joy in our hearts. Thank you Northern Lights Festival Boreal!”

As the festival looks toward the future and new generations, its legacy is secure, glowing as brightly as the Northern Lights for which it was named. See you again in a couple of weeks for another stroll down Memory Lane.

Jason Marcon is a writer and history enthusiast in Greater Sudbury. He runs the Coniston Historical Group and the Sudbury Then and Now Facebook page. Memory Lane is made possible by our Community Leaders Program.